Mac's Service Shop: Keeping up with New Components

|

|

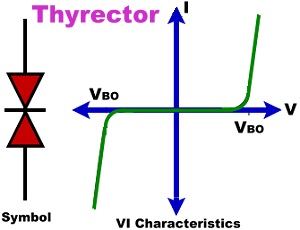

OK, I'm embarrassed once again. In this 1969 issue of Electronics World magazine, a device called a "thyrector" is mentioned the Mac's Service Shop episode entitled, "Keeping up with New Components." It was a totally new word to me. According to Wikipedia a thyrector is a type of transient voltage suppression (TVS) diode, aka a "transil" (another unfamiliar term). Maybe I have heard of both of them, but if so, I don't remember. You might think with all the vintage electronics magazine I have read, along with having been in the field since the 1970's, this wouldn't have caught me by surprise. Interestingly, the title of the article does not mention that it is a Mac's Service Shop story, but it is. Anyway, enjoy the story. Mac's Service Shop: Mac's Service Shop: Keeping Up with New Components

Business at Mac's Service Shop was becalmed in the February doldrums. Pocketbooks were still suffering from the Christmas trauma, and taxpaying time had begun to loom darkly on the horizon; so customers were having only essential service work done. Mac and Barney had cleaned and re-arranged the entire shop; they had checked and recalibrated all their test equipment; but now they were entirely caught up. Mac sat on a stool, chin in hand, trying to think how he could keep his restless red-headed assistant gainfully employed - or just employed. Suddenly he slid off the stool and took three bright-red display cards from a cabinet and placed them, together with a thick, paper-bound manual, on the bench in front of Barney. "What are those nasty-looking things?" the latter asked, peering suspiciously at the various small components contained in formed pockets of the clear plastic covers of the cards. "They are Experimenter's Kits put out by RCA last fall. That large card contains five diode rectifiers, an n-p-n silicon transistor, a p-n-p germanium transistor, and a heat-sink-mounted silicon controlled rectifier. As explained in the manual, these constitute the major items used in the construction of the basic universal motor-speed control and lamp-dimmer unit. The other two cards contain add-on kits to be used with the basic unit. A photocell in the light-sensor kit permits conversion of the basic unit into a light-activated switch. Three thermistors of different ranges and special solder for mounting them contained in the heat-sensor kit allow changes in temperature to control devices plugged into the basic unit.

"You mean you intend for me to build up these gadgets?" "Right. Most of them can be put to good use right here in the shop. The motor-speed control will work fine with our electric drills. The light dimmer, light-activated switch, and electronic flasher can all be used to create crowd-stopping displays in the front window. The electronic overload switch is just the ticket to monitor power drawn by a cooking intermittent TV set and to cut it off when something fails and the power consumption rises above the normal level. And one of the thermistors can be placed in a critical cabinet area or fastened directly to a component so that the set will be automatically switched off if the temperature rises above a preset value. But you don't need to limit yourself to the devices described in the RCA manual," Mac concluded, taking another manual from the cabinet and handing it to Barney. "Gee, how lucky can a guy be?" Barney asked sarcastically. "That's the 'Silicon Controlled Rectifier Hobby Manual' put out by G-E," Mac explained, ignoring Barney's sarcasm. "It contains construction information on several other interesting SCR devices you can build and tryout during your spare time here in the shop. I'll be especially interested in seeing you check out various suggestions in the manual for getting rid of radio interference created by the abrupt turning on of the controlled rectifier during each cycle or half-cycle. Also, you will find that thyrectors are used across the line to suppress transients that might damage the rectifiers, that light-activated switches are described, and that unijunction transistors are used. Experimenting with the apparatus described will give us an opportunity to observe the behavior of all three devices. And some of the equipment in this manual employs zener diodes. While we both know how zener diodes work and encounter them more and more frequently in the transistorized equipment we service, it won't hurt either of us to play around with them in experimental equipment where we can observe and measure their voltage-limiting action under deliberately induced extreme conditions." "I think I'm beginning to see what you're driving at," Barney mused. "You're not primarily interested in using the devices you want me to build. What you really want is for me to obtain some first-hand experimental knowledge of various types of semiconductors and related members of the 'istor' family that will be of use to me in the servicing of home and industrial equipment." "Precisely!" Mac applauded. "We both know there's a big difference between learning about a new component from reading about it and from actually working with it. Back in the early days of servicing a technician was invariably an experimenter, too. When he wasn't working on a customer's receiver, he was building his own and trying to improve its performance. Every time a new tube or a new circuit or a design for a new antenna came out, he was quick to try it out; and a great deal of what he learned from this experimenting was of great practical value to him in his service work. "But nowadays things are different. Very few present-day service technicians do any experimenting or any construction worthy of the name. We excuse ourselves by saying we're too busy to 'fool around' with new components and that we can learn all we need to know about them when we encounter them in new equipment. That's a little like a doctor's claiming he can learn all he needs to know about new diseases by treating them in patients. who bring these diseases to him. He can learn, all right, but it's likely to be rough on the patient and very time-consuming. "Just as a doctor learns about the human body thoroughly by dissection and keeps himself abreast of new techniques by sitting in on new operations, so the technician should keep himself thoroughly informed on the capabilities, weaknesses, and peculiarities of new electronic components used in equipment he intends to service by experimenting with these new components as soon as they are made available at reasonable prices - before they are incorporated into new electronic equipment for home and industry. "Many manufacturers are aware of this, and they are doing what they can to help the technician by bringing out kits and manuals such as those on the bench. Leaflets describing the parameters of new semiconductor devices and showing possible applications of these devices can be obtained free of charge from practically any manufacturer as soon as the devices are introduced. The technician who obtains a leaflet and one of the devices and experiments with it will be in a position to approach a piece of equipment using one of the devices with complete confidence. He knows what it is supposed to do, and he is familiar with any peculiarities or weaknesses it may have. He will be prepared to decide quickly whether a defect in that particular component is causing the trouble with the equipment or not." "You're making sense," Barney admitted. "I know for a fact that when I'm working on a piece of equipment containing an unfamiliar component, I'm always haunted by the possibility the trouble may lie in that little puzzler I'm not prepared to test." "I know what you mean. And we have to face up to the fact that more and more of these exotic devices are being used in ordinary home and factory equipment every day," Mac continued. "Controlled rectifiers have become cheap enough to be built into many drills, mixers, jig-saws, movie projectors, lamps, etc., and 1 think we've just scratched the surface of the possible uses for this versatile semiconductor. Our audio oscillator uses a thermistor in series with a capacitor across the load resistor of one of the amplifiers to hold the output nearly constant regardless of the frequency. And you know how often thermistors are used in liquid-level controls and temperature-monitoring devices in industry. Voltage-variable capacitors are used to vary the b.f.o. of communications receivers and to provide delta tuning of the receiver circuits of several ham and CB transceivers. They are also used to provide frequency sweeping of signal generators and in a.f.c. circuits. Photocells are almost as common as flashlight bulbs. They do everything from opening huge garage doors to adjusting the iris opening of even small and inexpensive cameras for the proper exposure." "You needn't beat the subject to death. 1 get the picture," Barney interrupted. "You furnish the jazzy electronic components and the spec sheets, and I'll certainly whip them up into circuits and put them through their paces. I really enjoy building and experimenting. What's more, I'll even let you look over my shoulder while I'm doing it so that I won't be the only hep guy in the shop. But now, if you don't mind, I'd like to get started putting this motor control and lamp dimmer together. Mac nodded agreement, and Barney, humming "Getting to Know You" slightly off-key, started to work.

Posted August 24, 2022 Mac's Radio Service Shop Episodes on RF Cafe This series of instructive technodrama™ stories was the brainchild of none other than John T. Frye, creator of the Carl and Jerry series that ran in Popular Electronics for many years. "Mac's Radio Service Shop" began life in April 1948 in Radio News magazine (which later became Radio & Television News, then Electronics World), and changed its name to simply "Mac's Service Shop" until the final episode was published in a 1977 Popular Electronics magazine. "Mac" is electronics repair shop owner Mac McGregor, and Barney Jameson his his eager, if not somewhat naive, technician assistant. "Lessons" are taught in story format with dialogs between Mac and Barney.

|

|

by John T. Frye

by John T. Frye  "The manual explains in great detail how fourteen

different control devices can be built from these three kits, but it does much more

than that. It goes into the theory of diodes, transistors, and silicon controlled

rectifiers in a thorough manner; it describes simple circuitry for testing every

component furnished with the kit and for testing sub-assemblies of the basic unit;

and it shows normal scope traces to be found at various points in the silicon controlled

rectifier circuit with various levels of the controlling signal. The construction

of a two-transistor regenerative 'triggered switch' is given and the action explained.

I particularly like the manual because the actual construction information is simple

and yet detailed enough so that almost anyone can build and use the devices; nevertheless,

the theory of operation is not 'watered down' below the technician level. When you

finish constructing, testing, and understanding the devices described, you'll know

a lot more about the practical use of silicon controlled rectifiers, photocells,

and thermistors than you do now."

"The manual explains in great detail how fourteen

different control devices can be built from these three kits, but it does much more

than that. It goes into the theory of diodes, transistors, and silicon controlled

rectifiers in a thorough manner; it describes simple circuitry for testing every

component furnished with the kit and for testing sub-assemblies of the basic unit;

and it shows normal scope traces to be found at various points in the silicon controlled

rectifier circuit with various levels of the controlling signal. The construction

of a two-transistor regenerative 'triggered switch' is given and the action explained.

I particularly like the manual because the actual construction information is simple

and yet detailed enough so that almost anyone can build and use the devices; nevertheless,

the theory of operation is not 'watered down' below the technician level. When you

finish constructing, testing, and understanding the devices described, you'll know

a lot more about the practical use of silicon controlled rectifiers, photocells,

and thermistors than you do now."