Lost Your Money? Wire KUBIT

|

|

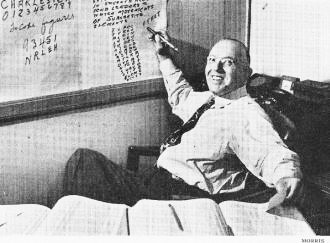

Sending telegraph messages, whether by wire or wireless means, has always been expensive, particularly considering charges are determined by the character (letter, number, symbol). Accordingly, the Shakespearean line from Hamlet declaring that "brevity is the soul of wit" can be reworked to "brevity is the soul of economy." A telegraph wire, unlike a telephone call, is a legally binding communiqué, as is of course a written letter, but a telegram is immediate transmission of information for time-critical messaging. A series of 'commercial codes' were developed enabling senders to save often significant money by sending multi-character codes that represented entire phrases and/or sentences. What struck me about this article that appeared in a 1948 issue of The Saturday Evening Post is how, following a court case involving how the inadvertent swapping of two character positions in a code caused a significant monetary loss by a company, a scheme for creating commercial codes was devised that assured at least two characters changed within each code within each message. It reminded me of "Gray code," developed by Frank Gray (patent US2632058 A) to minimize the effect of erroneous decoding while switch flipping, in digital sequences whereby two successive numbers only change by a single bit. You'll need to read the story to find out who won the lawsuit, and why. Lost Your Money? Wire KUBIT By Paul D. Green Commercial codes, like double talk and nuclear fission, require a lot of understanding. To the average person, the oddly combined letters, GAHGU, appearing in a business telegram, might suggest approaching nausea. But to men like William J. Mitchel, who know commercial codes, these letters stand for "cod-liver oil." Similarly, the letters AAAAA, in code language, mean "goose feathers, No.1 grade," and the letters ZZZZZ mean "bamboo steel." Between these combinations are 456,000 other possible combinations, which may mean anything from a single word to a whole page of text. In twenty-six years of code building, Mitchel has sold some 40,000 general business codes at from forty to seventy-five dollars each. In addition, he has made private codes for more than 300 large firms, including Standard Oil and General Motors. His largest private code contained 400,000 five-letter combinations, took two years and nine assistants to assemble, and cost the silk-importing firm that ordered it $100,000. Military and diplomatic codes are in an entirely different field; they are so much more complicated that only during wartime does the Government bother to censor commercial codes. Commercial codes have two main purposes: to cut cable and telegram costs, and to make messages confidential. The cheaper business codes may be read by anyone willing to buy a code book; the more expensive private codes are carefully guarded, and code books are given only to trusted officials. The. saving in telegraphic charges through the use of codes is easily understood. For example, the five letter combination LIMUD stands' for the phrase, "Cannot return unless you prepay passage." PYTUO means, "Have collided with an iceberg," and KUBIT means, "Have lost all my money." There are more pleasant messages in any commercial code book, but the general idea is to make a few letters do the work of many words. Happily, the telegraph companies smile on this effort, and encourage code users by giving them a 40 per cent discount. The discount, plus the saving of words, explains the great saving. As codes are handled by humans, occasional mistakes crop up. Years ago a Brazilian castor-bean grower wired a New York merchant the code word NFHIU, which means, "Cannot sell." The message, jumbled en route, arrived as NHFIU, which means, "Sell, if you cannot do better." The merchant sold, and the castor-bean grower lost a lot of money. The Supreme Court has ruled that the telegraph company isn't responsible for such mistakes. Most of these errors happened because there was only a one-letter difference in every five-letter combination. Then William Mitchel revolutionized the commercial-code business by trotting out a code that had two letters different in every combination. From this solid springboard, he jumped to become head of the Acme Code Company, with offices in London, New York and San Francisco, and to be considered by many the top commercial-code man in the world. Here's how the codes operate: The sender uses the subject index of his code book to find the phrase and code equivalent he needs for his message. The receiver simply takes his code book and runs down the alphabetically listed combinations until he finds the right one. Mitchel often is asked to decode personal messages. He thinks the saddest words of code or pen came to him when he decoded one that a young lady received from a man she obviously knew not wisely, but too well. It read: "I am giving you up for my wife."

Posted March 16, 2021 |

|