Solving a Broadcaster's Dilemma |

|

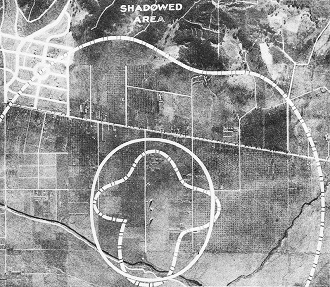

Here is a story of a real feat of RF engineering where the stakes were high for determining the cause of the problem and effecting a solution. In this case Bell Telephone Laboratories was solicited to figure out why a commercial broadcast station's signal was not being received as strongly as predicted after the station had relocated its facilities specifically to address the issue. A lot of power was being pumped into the antenna, but inexplicably some relatively nearby listeners were getting lousy reception while reports were coming in of good signal strength from hundreds - even thousands - of miles away in other directions. A modern antenna design program like EZNEC could immediately predict the empirically measured pattern if the entire system is modeled properly, but it would still require the insight of a really experienced engineer or technician to ascertain the cause. It makes you wonder whether, presented with the same challenge, you would arrive at the correct conclusion. Many options for a solution were ultimately presented to station management. The one chosen was the most technically elegant and, had it not been selected, would have denied the RF broadcast world an important example of the right way to solve problems - both from an engineering and a management standpoint. Solving a Broadcaster's Dilemma The country surrounding KNX's transmitter mapped by a Fairchild ship. The clover-leaf outline indicates the field before new insulators were installed. The oval shows the result of the change which redistributed the field to the nearly perfect circle of theory. The largest curve illustrates the effect of the Santa Monica Mountains upon the station's radiation By C. S. Gleason Problems That Arise in Connection with Receiving Sets Are Really Insignificant in Comparison with Those of Broadcast Station Operation. The great majority of listeners have little occasion to learn about the inside problems which arise in the efficient operation of a high-power broadcast station, and, providing no interruption occurs during the enjoyment of a favorite feature, they probably care even less. But let a break occur, and their first move is to telephone the station to know "why." Some even are stirred to put their thoughts - or at least some of them - on paper in no uncertain terms, for the benefit of the station manager. Mr. Gleason, the author, tells here the story of how one station, out on the west coast, after moving to improve its service, found that the local area was not being served as well as before the change. Simple though the trouble appeared to be, it required a good deal of time and labor to track it down. Although not intended particularly for the guidance of station managers, this article will undoubtedly open up to them new lines of thought. At the same time, it will give to broadcast listeners some inkling of the tremendous problems which beset the station manager in his efforts to remain on the air "on schedule." Trouble was brewing at KNX, and wise studio underlings, seeing the storm clouds gathering about the station manager's brow, were scurrying to cover. True, reports trickled in constantly from the forty-eight states of the Union, from Canada, Mexico, Cuba, and Alaska, with a fair sprinkling of acknowledgments from Australia, New Zealand, Japan, England, and various South Sea islands. But listeners in parts of the surrounding area, including the northeastern suburbs of Los Angeles, had reported that KNX was not coming in as well as before it had moved its transmitter from Hollywood to a point in San Fernando Valley, seven miles away, where it is operated by remote control from the studio on the Paramount Pictures' lot. And when things begin to happen to the local service area there is bound to be trouble. Broadcasters must fully cover the local area whether distant listeners are served or not; and it was the desire of the owners of KNX that their station blanket Southern California with a bumping signal amply strong to override static and atmospherics at all times of the year. Technicians scratched their heads. The usual number of amperes were going into the antenna, and field strength tests showed 15,000 microvolts per meter at Santa Monica, 15 miles away. But up at Altadena, about 25 miles removed in a straight sweep up the valley, the intensity was somewhat less than the 10,000-microvolt level set up by engineers as a standard for "excellent, year-round loudspeaker reception." And when Naylor Rogers, station manager, called his technicians into his office and in a few well-chosen words delivered an ultimatum to the effect that something was wrong and that the technical honor of the station depended upon their finding out what it was, things began to move rapidly.

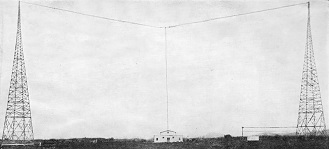

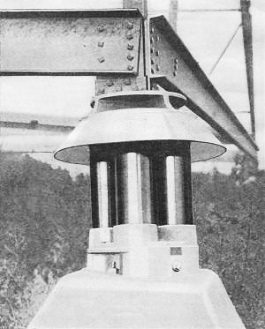

Upon a geological survey map showing the contours of the surrounding district, a circle was traced around the station's location, with a radius such that the circumference followed, as closely as possible, existing boulevards. This represented the ideal field distribution. Then, with the transmitter at KNX running at fixed output, a point on the circumference of this circle was selected. Here a special shielded superheterodyne was tuned to KNX's wave and the reading of a milliammeter placed in the plate circuit of the second detector was noted. Then a local oscillator was substituted a the source of current, and the intensity of it, output adjusted until the milliammeter reading was the same as before. The oscillator output thus measured KNX's field strength. At various points within the circle other readings were taken. By the time the circuit was completed and the readings plotted upon the map. with the points of equal field strength connected by a smooth line, the resultant figure was far different from the perfect circle of ideal distribution. The general trend of the loops and kinks was roughly toward a figure-eight, with several minor bulges giving a clover-leaf effect. Evidently the radiation was most effective in a line running approximately crosswise to the valley and down to the ocean. But over a sector N. 130° E. and over most of Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the radiation was weaker - about 67% of that to the east and south, in which direction lay the Santa Monica Mountains, a long, low range running north-northeasterly down to the ocean, and attaining a height, at some points, of approximately 1,400 feet. The towers of Station KNX after insulators have been installed in order to minimize their absorption effects. Mr. Hovgaard knew that mountains, as well as skyscrapers and city areas, have a pronounced screening effect. This effect he set about to measure. Over the few existing roads through these mountains - many of them hardly more than trails, rough and crevassed by the rains - went the field car. Measurements were taken at points on an ever-widening spiral. terminating at last beyond the mountains. And when the results were plotted upon the map, it was found that on the far side of the mountains the signal strength dropped sharply, the shadow effect in places reaching as high as 60%. The outlook for improving reception was not bright, since it was not considered practicable to change the physical features of the topography so as to straighten out the clover-leaf into a nice. symmetrical circle. Boundless as was Mr. Rogers' faith in the ability of the Bell engineers, it was not sufficient to move these mountains. But Mr. Hovgaard did not believe that this told the whole story. The intensity on the side away from the mountains was also low. Why should there be a shadow where there was nothing to cast one? So he set out on another series of tests. The frequency was lowered to 700 k.c., and a new curve was plotted. "Aha!" exclaimed Mr. Hovgaard. "The plot thickens!" The distribution of the field, while not perfectly uniform, was at least ovular in shape. And the reason, deduced Mr. Hovgaard, was what he termed "tower resonance." Now the antenna at KNX, as will be seen from the photo, is a single vertical, six-wire cage 179 feet long, swung between two graceful steel towers 225 feet high and 550 feet apart. It so happened that the natural period of the tall slim masts coincided very closely with the frequency assignment of KNX: namely, 1,050 k.c. The towers therefore acted as resonant circuits, and a large current was easily induced in them by the passing wave, with the result that the field was greatly distorted in that direction. In his report, Mr. Hovgaard summed up he situation briefly as follows - that the trouble was due to four causes: (1) Directive and inefficient performance due to tower resonance. (2) High attenuation by the Santa Monica Mountains. (3) The relatively highly carrier frequency. (4) The relatively great distance of the station from the local areas to be served. Although it is true, he said, that greater distance of transmission had been obtained more easily on the shorter waves, it is also true that for local service, which depends upon the "ground wave," the lower frequencies are attenuated less with distance and so can serve larger areas dependably. Given equally powerful stations and equally efficient antenna systems, the signals at fifteen miles' distance from a station on 1,050 k.c. will be 15% lower than from a transmitter on 700 k.c. At greater distances, this effect is even more pronounced. The intensity of the ground wave falls off rapidly with distance: for example, on 1,050 k.c. it will take only one kilowatt of power to produce the same signal as will be heard at 15 miles with five kilowatts output. The one-kilowatt signal at three miles is four times as strong as that from a five-kilowatt station at fifteen miles. Therefore it is a good thing to get as close to the area to be served as possible, bearing in mind, however, that too close proximity to business districts may result in high attenuation and "shadows" cast by tall, steel-frame buildings. "Well, what are the remedies?" Mr. Rogers wanted to know. "There are a number of possible solutions," replied Mr. Hovgaard. "First, you can move closer to the city. That is expensive. Second, you can increase your power, provided the Radio Commission will let you. That is cheaper and has the advantage that at the same time your distant service range is increased. Third, you can change your carrier frequency - with the consent of the Commission, of course - from 1,050 k.c. to 720 k.c. or less. This will avoid resonance with the towers, and will improve the field strength in the more important areas by about 100% - an audio frequency improvement of about twelve decibels. Fourth, you can erect a new and larger antenna with two 350-foot steel towers 700 feet apart and mounted on insulated footings, which will break up the electrical circuit of the masts and prevent resonance with the carrier. If you do this, you may expect an improvement of 180% in the Beverly Hills region and about 40% in other directions. Or you can reduce the height of your present towers, in order to reduce their natural period until it no longer approaches your transmitting wavelength. By lowering the towers to 150 feet the resonant frequency would be shifted to about 1,500 kilocycles. Sixth, you can doctor up the masts and change their resonant frequency by loading them electrically with inductances; this is not a sure cure nor entirely effective. A multiple-tuned antenna would get around the difficulty, but it would be expensive for the amount of improvement it would give. Lastly, you can insulate the footings of the present antenna by installing insulators, thus breaking up the electrical circuit. This would give you an improvement of 50% in Hollywood and Beverly Hills - an audio gain of seven decibels." "Well," said Mr. Rogers, "we know we don't want to move. We have had trouble enough finding our present location without breaking up housekeeping and moving again. Even if we should increase power, we would still be resonating with the towers. We want to make the most of the wave we radiate. To get a new frequency assignment would at least take time, if it were possible. We don't want to wait, nor do we want to rebuild our antenna if it can be fixed up as it is. It would be too bad to spoil our beautiful towers by cutting them off at the top. Your sixth and seventh solutions you yourself do not regard as very satisfactory. What about insulating the present masts?" "It can be done," replied Mr. Hovgaard. "Do it." said Mr. Rogers. The Ohio Brass Company set to work upon the design of a new insulator to meet the specifications of the technicians. They brought forth a pattern consisting of four round brown porcelain columns grouped together between heavy steel plates, with a large shield at the top to keep out the weather. At the base was provided a chamber with an outlet normally sealed by a steel plug, which can be unscrewed, so that in case moisture should cause the insulators to leak, compressed air forced in at this opening would soon dry them out. Eight of these sturdy units were shipped out to KNX and a local steel company sent over a crew of men to install them. The results of the change were gratifying. Not only did testimonials indicate that local listeners were getting better service, but measurements showed that field distribution much more nearly approached the ideal circular form. A large, densely populated area of Los Angeles and its extensive environs was thus, in effect, moved a number of miles closer to the transmitting station. The work of broadcasting bigger, better and brighter bedtime stories once more went on apace.

Posted January 9, 2023 |

|