Nomorule: A Complete Calculator on a Sheet of Paper

|

|

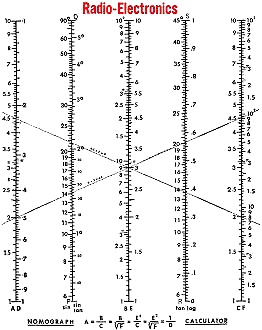

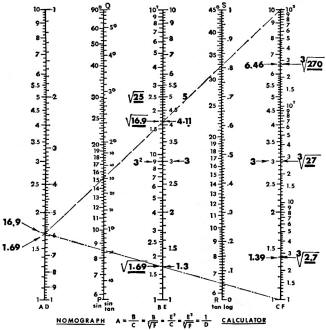

Nobody really needs a printed nomograph these days given the ready availability of hand-held calculators, smartphones, and laptop and desktop computers. The upside of other than a nomograph is that results are more generally more precise with less possibility of error, and the user does not have to keep track of the decimal point location. The downside is that there is no visual cue as to how the inputs interact to produce an output. A nomograph, as presented in this 1967 Radio−Electronics magazine article, uses points on two indexed scales to intersect a corresponding result on a third scale. The user can easily see how varying one or both values affects the output. The nomograph can just as easily be used to calculate a required input or inputs to arrive at a desired output. For instance, calculating the equivalent resistance of two resistors connected in parallel, governed by the equation Req = 1/(1/R1 + 1/R2), is not an easy mental exercise, unlike with resistors in series, governed by Req = R1 + R2. Using a nomograph, you locate the value of each resistor on the two respective scales, then use a straight edge to find where it intersects the resultant resistance scale. Conversely, if you you need a particular Req and you have an assortments of resistors from which to make that value, you simply lay the straight edge on the Req point and then pivot it across the two input resistance scales to find a pair of values that are available to you. See Nomorule Part 2 in the April edition. Part 1 - Use it wherever you would use a slide rule. Keep your results as long as you like! A portable computer on paper for desk or workbench.Fig. 1 - This is the Nomorule. Simply cut it out, back it with cardboard, and you're all set for calculations. By John H. Fasal* You've probably had it drummed into you by now that a slide rule is a tremendous time and labor saver for anyone who works with numbers. But do you use one? Whether you do or not, you're in a bit of a bind if you work in several places. You can have several slide rules, or you can carry one with you. The first is expensive, the second a nuisance. For you, here is a calculator - with a memory, yet - one that you can fold up and put in your pocket, make copies of for all your working places, distribute to your friends, scale up or scale down as you please. Make a few copies right away; when one gets dirty and dog-eared, throw it away and use another. We call it "Nomorule." Actually a generalized nomograph calculator, the Nomorule has one big advantage over a slide rule: memory. You can "store" mathematical operations as long as you need them for comparison and checking. Radio-Electronics has set up the Nomorule so you can simply cut it out and use it immediately, just as it is. But to keep it neat and accurate, you'll want to protect it. Nomorule (Fig. 1) should be cut from the pages of this magazine and cemented to a hard surface, such as a Bakelite board. Cover with a sheet of matte-finish Mylar or acetate (art supply stores), frosted side upward. The Mylar should be held firmly by a spring-loaded clamp fixed to the board. The scales must be well visible through the Mylar, so that you can trace alignments in tiny pencil lines on the frosted surface.

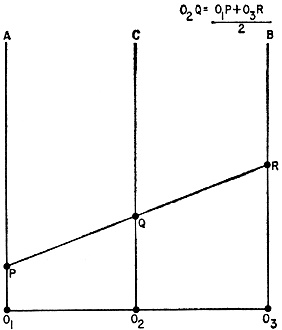

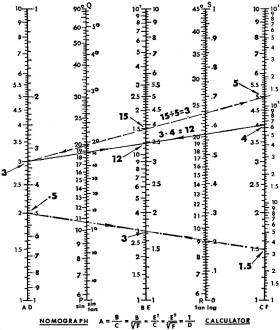

Fig. 2 - Principle of the Nomorule: Length O2Q is arithmetic mean of O1P and O3R. Hence O2Q represents geometric mean. Fig. 3 - Some simple examples of multiplication and division you can easily perform. After you complete a problem, just remove the alignment tracings with a damp sponge, or erase with a soft eraser. If you want to keep the solution for further reference, you'll have to put at least two reference points on the Nomorule and the Mylar cover. Line them up perfectly before starting to "read out" the chart. Fundamentals Here are some of the principles on which Nomorule is based. You can find the product (or quotient) of two numbers, A and B, by adding (or subtracting) their logarithms, like this: log (AB) = log A + log B log (A/B) = log A - log B log Am = m (log A) = -m (log(1/A) ) logn √A = (log A)/n In a nomogram, we add and subtract logarithmic calibrated scales geometrically, rather than by moving a slider within a frame as in a slide rule. Consider a simple nomograph with vertical scales A, C, B, (Fig. 2). All scales are identical and equally spaced. Let a straight line intersect the scales at P, Q, R. Then the section O2Q equals one-half the sum of sections O1P plus Q3R. If the scales are logarithmic we have the relation, Q = √(P x R.) If we are interested in a product only (not its square root) we can change the calibration of middle scale C. We make its modulus, or unit length, equal to one-half the modulus of the other scales. Then log Q = log P + log R, or Q = P x R, directly. The reciprocal of a number comes easily by using the two sides of the first scale, A and D, in Fig. 1. For example, D = 0.5 = 1/2, and A = 1/D = 2. The reverse, then, is also true - i.e., D = 1/A. Dividing by a number is the same as multiplying by its reciprocal. From B = AC, we get B/A = C which then becomes BD = C, since 1/A = D. The dotted line shows that 9 x 0.5 = 4.5, or BD = C. Squares and square roots come out of scales B and E, cubes and cube roots from scales C and F. Other relationships, including trigonometric and logarithmic functions, can also be read off. We'll come to that in a moment. Basic Operations Once you know the basic rules, you can handle any combination of operations quickly and easily, and with sufficient accuracy for most practical problems. Multiplication: Connect 3 (on A) with 4 (on C) to find 12 (on B). This is shown in Fig. 3, solid line. Division: To find 15/5, intersect 15 (B) with 5 (C) to get 3 (A). This is shown by the dashed line in Fig. 3, and uses the equation B/C = A. Note that we chose 1.5 on the higher decade of B, above the 10, so it actually represents 15. Another way to divide is to apply the equation B = C/D mentioned earlier. Intersect 1.5 (C) with 0.5 (D) to obtain 3 (B) shown by the dot-dash line. Finding the Decimal Point Like a slide rule, the Nomorule determines numerical values, not the decimal position. But, as with a slide rule, finding the decimal point is easy. Numbers can be expressed as some value between 1 and 10, multiplied by some power of 10. For example: 13,200 = 1.32 x 104 0.0061 = 6.1 x 10-3 To multiply these numbers, express the product as 1.32 x 6.1 x 10(4-3). Using the nomorule, we find the answer is 8.05 x 10 = 80.5. To divide 975 by 0.0003, express the numbers as (9.75 X 102)/(3 X 10-4) and we obtain 3.25 X 106 = 3,250,000. As before, division of the significant digits is handled by the Nomorule. This result is multiplied by the proper power of 10. Squares and square roots are read directly from scales B and E. Fig. 4 shows that √25 = 5, and that 32 = 9. Now let us find 1,2002. Write 1.22 x (103)2 = 1.44 x 106 = 1,440,000. To find 0.0032, write 32 X (10-3)2 = 9 x 10-6 = 0.000009. Take special care in extracting square roots. To find √169,000. first split the number into groups of two digits each, beginning with the decimal point. This points off a number between 1 and 100, whose square root must lie between 1 and 10. Thus, √169,000.= √16|90|000. = √16.9 x √104 = 4.11 x 102.We cannot write 1.69 or 169, multiplied by some power of 10. Likewise √0.0169 is written √0.01|69 = √1.69 x √10-2 = 1.3 X 10-1. Squares may also be found by using scales A and E in conjunction with point 1 (C). For example, the dot-dash line (Fig. 4) shows that √16.9 (A) = 1.3 (E). The reason? We know that A = B/C and that B = E2. Then A = E2/C. When C = 1, A = E2 directly. The same figure shows 4.112 = 16.9, if we use 10 (C) as pole. We have used the equation A = E2/ 10 in this case, so the answer on A (1.69) must be multiplied by 10 to arrive at the correct solution, 16.9. C and F determine cubes and cube roots directly. Note that F has three decades, and we must use the correct one. For example, 2.7 is in the first decade, 27 in the second decade, 270 in the upper decade. For cube roots of large numbers, first split the number into groups of three digits, beginning with the decimal point. For example, 3√270|000.= 3√270 x 3√103; also 3√0.002|700 = 3√2.7 x 3√10-3. Then extract the roots. Part 2 of this article will continue with scale transfer, trig functions, and other topics. To Be Continued * Assistant chief engineer, Alarms Engineering, Walter Kidde Co., Belleville, N. J.

Posted March 11, 2024 |

|