Modern Theory of Electricity

|

|

Modern Theory of ElectricityWhen radio beginners attempt to grasp the entire theory of electricity at one sitting, they become hopelessly confused. It is the purpose of this series of discussions to lead our readers along in easy stages, until they really grasp the principles. Part I The nature of electricity is not really understood, any more than the nature of thought. Electricity is an unseen force. Its presence is known by its actions. Yet a great deal more is known than was the case twenty years ago, and fresh discoveries are being made every day.

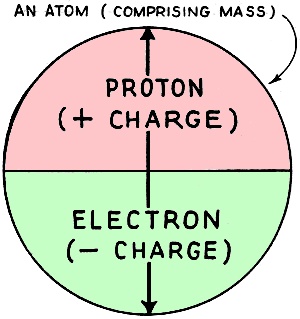

Fig. 1 - Electrical constituents of an atom. The modern theory of electricity is termed the "Electronic Theory." This is not so difficult to understand as it sounds, and is of the greatest possible help in explaining the action of tubes and other electrical phenomena. Our present theory concerning the structure of the atom completely sums up all known facts concerning electricity. Scientists may form a mental picture of an atom to help them to explain one electrical phenomenon, which may be quite inaccurate for dealing with another problem, and a new mental picture of the atom may have to be adopted. The reader must realize that it is impossible to indicate in a few paragraphs all the difficulties and limitations met with in the study of "Molecular Physics," but a brief summary of some of the modern conceptions of the constitution of atoms may enable him to get a good idea of what is occurring. For the student to thoroughly comprehend the "Electronic Theory" and its application in radio and sound equipment he must stop to study a little radio history which will date back in this case to the late Thomas A. Edison. As you will remember he was the inventor of the incandescent electric lamp, made luminous by heat, the first of its type being commonly known as the carbon filament lamp. This became very popular as the method of illumination and was then used extensively in offices and workshops. Although this lamp was the greatest gift to mankind its uses were limited to illumination. In other words, just another light. We will now turn our attentions to Prof. J. S. Fleming of England, who watched with interest the dark film that began to collect on the inside of the glass bulb after the lamp was used, and nearing the end of its normal life. This film that collected cut down the candle power of the lamp which naturally lost its efficiency and had to be replaced. Professor Fleming analyzed the film coating and found it to contain carbon. He supposed that the carbon was given off by the filament, when the lamp was in use, and with further experiments he proved that when the carbon filament was hot it liberated minute particles of carbon that collected on the glass walls of the lamp. This phenomenon was, however, invisible in its action, but in time showed tangible clues of what was taking place in the lamp when the filament was hot. This discovery opened the gates to unlimited possibilities regarding its use, and revolutionized the whole science of radio. It will now be necessary to investigate these small particles, to find out their reasons in allowing themselves to become detached from the body of the filament and travel into space. Matter The students must first of all understand that matter is anything that occupies space and has weight. The three forms of matter known to us are under the following category: Solids - such as steel, iron, wood, wax, porcelain, paper, etc. Liquids - such as water, mercury, oils, etc. Gases - such as hydrogen, oxygen, air, coal gas, etc. The construction of matter is fairly well understood. Matter is composed of myriads of distinct or separate particles, with spaces between them. These particles are termed molecules. There are as many different kinds of molecules in the universe as there are different kinds of substances. The Molecule A molecule is the smallest portion of any substance which cannot be subdivided further without its properties being destroyed. It is the smallest complete and normal unit of any substance. The Atom The molecules are made up of smaller particles called atoms. An atom is the smallest unit particle into which matter can be divided by chemical separation. A molecule may consist of one, two, or more atoms of the same kind, or it may consist of two or more atoms of different kinds. Thus two atoms of hydrogen (H) will combine to form a molecule of hydrogen (H2). Two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen will combine to form one molecule of water (H2O). The number of atoms in a molecule varies with the substance. In a molecule of salt there are two atoms, in a molecule of alum there are about one hundred atoms, etc. Different kinds and combinations of atoms can be arranged in an endless variety of ways to form different substances - different kinds of matter. It is believed that there are no more than 93 different kinds of atoms; and molecules of all known substances consist of combinations of these atoms. The next consideration is the construction of the atom. One conception of an atom is as a nucleus, charged with positive electricity, around which revolve in fixed orbits negative electrons, as planets around a central sun. An atom is thus pictured as comprising from one to a number of electrons which are interlocked and revolving at inconceivably great speeds in regular orbits around the positive nucleus. Thus it is apparent that energy is associated with and locked up in every atom. (Fig. 1) The Proton The nucleus may he thought of as a charge of positive electricity or "proton" concentrated at a point. at the center of the atom, around which the electrons-restrained in their orbits by it - revolve. (Fig. 1.) We know very much less about the positive nucleus than we do about the electron. It may consist of several positive units of charge - or positive electrons - locked together in some manner by the help of the negative electrons, but the nucleus as a whole must have a positive charge to hold the atom together. The Electron It is believed that atoms are made up of minute particles of negative electricity - termed "electrons" - and of a central nucleus in which practically the whole mass of the atom resides. The number of electrons in the universe is constant and unvarying. Electricity can neither be created or destroyed. Electrons can be set in motion and caused to be moved from one location to another. thus producing what are known as electrical phenomena. The "E. M. F." But electricity or electrons - can be neither made nor eradicated. It is therefore evident that electricity can be neither "produced" nor "generated" in spite of the fact that the term "generation of electricity" is frequently used. When a statement is made that "electricity is generated by a battery or dynamo" what is really meant is that the battery or dynamo is forcing some of this electricity, which is already in existence, to move. It exerts an "electro-motive" force (abbreviated e.m.f) measured in volts. A battery or dynamo does not generate electricity in the wires connected to it any more than a pump, which is impelling a stream of water in a pipe, generates the water. The dry battery and storage battery are two methods of exerting an electro-motive force, by splitting up the substances used into atoms by chemical separation. This will be explained later. The dynamo is another method of exerting an e.m.f., by cutting a copper conductor with magnetic lines of force; electricity and magnetism are so closely associated that when one is present the other plays an important part. Our next concern is atomic separation by chemical process. The existence of an electric current in any circuit means that energy in some form is being liberated at the generating source; and the continuance of this current necessitates the continuous expenditure of energy. In the case where the current is supplied by a dynamo driven by a steam or gas engine, the source of the supply is the coal and the place where the energy is being liberated is in the furnace. Coal contains large supplies of energy, which it readily liberates in the form of heat, and which, after such transformations, may appear in a circuit in the form of electrical energy, and is used for lighting, running motors, energizing radio sets, and can even be stored in batteries. The coal becomes oxidized or burned up in the process. and the quantity of energy that can be obtained is clearly limited by the amount of coal consumed or burned. In most cells the fuel consists of zinc and acid, which are consumed. but which, instead of giving out their energy in the form of heat, give it out directly in the form of electric current. A cell is in reality nothing more than a little furnace in which zinc instead of coal is used as a fuel, and in which the ''burning'' is not simple oxidation. Primary cells consist of three essential constituents for the production of e.m.f., viz., a positive plate, a negative plate, and an exciting liquid (termed the "electrolyte"). According to the nature of the plates and the liquid, a certain difference of potential (or "p.d.") is set up between the plates. When the cell is on closed circuit, i.e., when the plates are connected through an outside circuit, chemical energy stored up in the cell is converted into electrical energy. The general action of any type of primary cell may be briefly summarized as follows: The negative plate, generally zinc, dissolved gradually in the electrolyte, liberating hydrogen. The positive plate - copper, carbon, or platinum - remains unaffected, and a film of hydrogen gas accumulates over it. This collection of hydrogen gas bubbles is called "polarization." To prevent polarization (which increases the resistance of the cell, and sets up a counter e.m.f.) a fourth substance is used - termed a "depolarizer'' - in the cell to absorb the hydrogen. As we have seen before, however, the current really consists of an electron flow from the negative to the positive terminal. The conventional way of considering the direction of the flow of the electric current is from the positive to the negative terminal. Thus the negative plate supplies the electrons, which flow from it though the outside circuit to the positive plate, and through the cell to the negative plate, are set in motion by the chemical action of the cell. The e.m.f. or difference of potential (d.p.) between the terminals on open-circuit depends entirely on the substance used (the positive and negative plates, and electrolyte), and not on the size of the cell. A diluted solution of sulphuric acid in water or a saturated solution of sal ammoniac are commonly used as electrolytes. The resistance of the cell depends upon the area of the plates immersed, their distance apart, and the specific resistance of the liquid. The larger the plates, and the closer they are together, the less is the internal resistance. The advantage of a large cell is not in the value of its e.m.f., but in its smaller resistance, owing to the area of surface contact of the plates; also, it contains more energy stored in chemicals and lasts longer. (This instructive article is published by courtesy of R.T.G. News).

Posted October 31, 2023 |

|