Using the Decibel

|

|

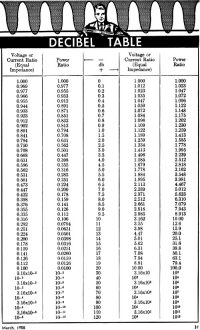

For some reason even a few really good technicians and engineers have problems with decibels. Ever since learning about, and truly understanding, logarithms, I have appreciated the convenience of being able to use addition and subtraction to perform multiplication and division, respectively. Decibels, being logarithms, have always made perfect sense to me. Even the difference between voltage dB's and power dB's has been easy to remember because of the power rule of logarithms, log (AB) = B x log (A). Calculators offer little help when you don't comprehend the basics of decibels. In 1955 when this article appeared in Popular Electronics magazine, people used tables of logarithms rather than punching calculator keys. Mathematicians and appointed underlings spent their lives generating tomes of logarithms. Historians have found many errors in those tables while doing research, but no ships ever sailed off the edge of the Earth due to a computational error based on them. On a side note, I recall a day when I was a teenager where I was listening to a distinguished lady who was the wife of a former assistant attorney general of the U.S.† (both he and his wife were Rhodes Scholars). My mother typed legal transcripts for him. I sometimes made a few bucks doing odd jobs around their sprawling waterfront property on the Chesapeake Bay. The woman knew of my interest in astronomy and mechanics and began talking about celestial navigation and how logarithms were of importance in precision excursions like cartography (map making); hers were the days before electronic navigational aids. I was mesmerized by the ease at which she conversed on the subject. After her somewhat lengthy dissertation, she pointed to a picture on the fireplace mantle (one of about 5 in the house) and asked me to hand it to her (she was bedridden). As I picked it up I immediately recognized the two people in it - Mrs. Littell as a much younger woman, and also none other than Albert Einstein! † Norman M. Littell and Katherine M. Littell Using the Decibel In any listening situation, the smallest increase in the volume of any sound that can be detected by the human ear is one-fourth, or 25 percent, over a previous sound. In other words, if any two sounds have a power ratio of at least 1.25 to 1, we will detect that the former is louder. This ratio holds true for a wide range of power regardless of the absolute power of a particular sound. If we hear two sounds whose powers are respectively 12.5 and 10 watts, we would still hear the same difference in their loudness as we heard between the sounds at 1.25 and 1 watt, since the ratio is still the same (1.25). This is because we hear approximately in proportion to the logarithm of the intensity, rather than in direct linear response to it. The decibel has been developed as a convenient unit for expressing and measuring. intensity logarithmically. Mathematically, "1 decibel" is approximately 10 multiplied by the common logarithm of the ratio, 1.25 to 1. The factor of 10 enters the picture because the original unit used was the "bel" (named for Alexander Graham Bell), which is the logarithm of 10 to the base 10. The decibel is actually one-tenth of a "bel" and is used in preference to the bel inasmuch as a change of sound intensity of 1 decibel approximates very closely the ratio of 1.25 to 1, which is the minimum change in sound intensity human ears can detect. The decibel is used widely in audio work because it represents accurately the response of the ear to different intensities and because it can be used over a wide range of intensities. Decibels are used for expressing power ratios, voltage ratios, current ratios, amplifier gain, hum level, loss due to negative feedback, network loss, and loss in attenuator circuits and in transmission lines. Gain is expressed as plus dB; loss as minus dB. Ratios between currents and voltages across the same or equal resistors are also expressed in decibels. In the case of voltages or currents, the logarithm of the ratio must be multiplied by 20. This is because the decibel is basically an expression of power (wattage) which is always a function of the square of either current or voltage. To square a number, you double its logarithm. Thus, in the case of values already expressed as powers (wattage), we multiplied the logarithms of the ratio by 10. But in the case of values not yet expressed as powers, such as voltage or current, we multiply the logarithm of their ratio by 10 doubled, or 20. We now can state all the above in terms of these simple formulas: dB = 10 log (P2 / P1) when P is known in watts. dB = 20 log (E2 / E1) when E is known in volts. dB = 20 log (I2 / I1) when I is known in amps. The value of the "common logarithm" (sometimes written as log10) is easily obtained from standard tables that are included in most mathematics and technical textbooks. From then on it's a case of simple arithmetic. The table on the opposite page is a shortcut aid in determining dB gain or loss. It has, in effect, already computed the logarithms of the power (and voltage and current) ratios for you. Notice that the right-hand side (4th and 5th columns) expresses ratios in which there is a gain (1 or higher). The left-hand side (1st and 2nd columns) expresses ratios in which there is a loss (1 or lower). The center column gives you the number of decibels of either gain or loss for a given ratio. Let us now work a few problems using both the formulas and the table. Example: What will be the gain in dB of an amplifier whose output power rises to 5 times its input? The formula tells us that for power (in wattage), dB = 10 log (P2 / P1) In this case, P2 over P1 is given; it is known to be 5. (In other words, the input might be 2, the output 10, resulting in a ratio of 5 to 1). The log of 5 is approximately 0.7. Multiplying this by 10, we get 7, which is the solution. In other words, this amplifier has a gain of 7 decibels. In practical terms this means that the difference in sound intensity between the input to the amplifier and the out-put from it would be heard by the ear as seven times the minimum change in loud-ness that we could detect. Now, let us use the table to work this problem. Since there is a gain involved, we refer to the right-hand portion of the table. Since the values are in terms of power (watts), we use the 5th column. The nearest figure in this column to our power ratio of 5 happens to be 5.012. This corresponds to plus 7 in the dB column. Again, our answer is plus 7 dB. Let us work a problem using voltages. Example: What will be the gain in dB of an amplifier whose output voltage rises to 9 times its input (across equal resistances) ? Here we must multiply the logarithm of the ratio by 20, since we are dealing with a voltage value rather than a wattage value. The common log of 9 is 0.95. Multiplying this by 20 we get 19 dB. Again, the same answer could be obtained directly from our table. Since a gain is involved we again confine ourselves to the right-hand side of the table. Since our ratio is expressed in voltage, we check down the 4th column. We find that the number of decibels that corresponds most closely to a voltage ratio of about 9 happens also to be 19 dB. As long as this table is available, there is no need for the formulas or for logarithmic values of the ratios. If the table is not handy, though, the formulas and a table of common logarithms will solve any problem. Let us now take a situation in which there is a decibel loss to be calculated. For example, an amplifier has a negative voltage feedback loop which is intended to reduce distortion at the output. This feedback voltage also reduces the overall gain of the amplifier. But by how much? Assume that we measure 1.2 volts at the output of the amplifier with its feedback loop in operation. Then we disconnect the feed-back loop and find the output measures 12 volts. Our ratio in this case is 1.2 over 12, or 0.1. We now consult the left-hand side of our table for decibel loss. Since these are voltages we check down the column so headed. We discover that a voltage ratio of 0.1 indicates a 20 dB loss. Thus we express the feedback value in this amplifier as minus 20 dB. Conversely, if an amplifier's specifications claim that the circuit incorporates a minus 20 dB feedback loop (or "negative feedback, 20 dB"), this means that the output of the amplifier should measure one-tenth the voltage with the loop that it does without the loop. Another example of decibel loss: Assume that an amplifier has a rated output of 20 watts. We want to determine what its hum level is because in order not to hear the objectionable hum, its level should be very low - maybe 50 dB below the rated output of 20 watts. Here's how this is done: We apply a signal to the input of the amplifier and connect a voltmeter across its output terminals, say the 8-ohm terminals. Next we turn up the gain of the amplifier to the point necessary to produce its rated 20 watts output. Since we are using a voltmeter at the output terminals, we must translate watts into volts. From Ohm's Law we know that power in watts is equal to the square of the voltage divided by the resistance. (P = E2/R) Therefore, E equals the square root of P x R. P is 20 and R is 8. Thus E equals the square root of 160 which is approximately 12.7 volts. Consequently, when our voltmeter - connected across the 8-ohm output terminals - reads 12.7 volts, we have reached the amplifier's rated output of 20 watts. We now disconnect the input signal and short the input. Naturally, the voltage to be expected with no input signal should be quite small. But whatever is present will be noise and hum within the amplifier circuit itself. Again, consulting our voltmeter (still connected at the 8-ohm terminals) we discover that it reads 3 millivolts (0.003 volts). To determine the number of "minus decibels" the hum level is with respect to the 20 watts output, we must first get our voltage ratio, which is 0.003 over 12.7. This comes to approximately 0.00024. Since we are dealing with a loss in voltage, we consult the 1st column of our table, and we find there is no figure like our 0.00024! Therefore. we must interpolate. The nearest significant figure to our ratio of 0.00024 happens to be 0.251. This gives us minus 12 dB. But our ratio is about one-thousandth, or 10-3, of 0.251. We, therefore, consult the 10-3 value in the same column and discover we must add another minus 60 dB to the minus 12 we already have. Thus our final answer is minus 72 dB. This means the hum level of the amplifier is 72 decibels below its rated output, which puts it well below the level at which it could be heard. Conversely, this means that if an amplifier is rated at 20 watts output with a hum level of minus 72 dB, the actual voltage measured across its 8-ohm output terminals with no signal input should not exceed 0.003 volts. Three main types of meters are used for measuring dB directly, without the need for calculating values by the use of logarithms or the table. The simplest and possibly the most familiar type is the "output meter" or the decibel scale found on many multimeters. This is actually an a.c. voltmeter calibrated to read the number of dB that expresses a ratio between the power being fed into the meter and some fixed reference level, usually 6 milliwatts. The meter calibration assumes that the voltage is measured across 500 ohms resistance. This type of meter is used in determining the relative outputs of various audio circuits and is also used in receiver alignment. The "VU meter" is similar to the output meter, except the reference level is 1 milliwatt in 600 ohms resistance. In addition, the VU meter has time-constant characteristics which determine its response to voltage peaks, such as "sound bursts" or other short time interval peaks. It is widely used in broadcasting and recording studios to monitor the output levels of programs. A third type of decibel meter is the sound level indicator. This is actually an assembly of a microphone, an amplifier, and an a.c. voltmeter calibrated to provide a dB reading which corresponds to human hearing levels. On this meter, zero dB represents the threshold of hearing. This meter is used by acoustics technicians to determine hearing conditions in auditoriums and theaters. In summary, the decibel is used to express any ratio of power, voltage, current, acoustic energy, etc. whether it be a gain relationship or a loss. It can be used to express the range of a symphony orchestra and then to determine how much amplification is needed to carry the music across lines of certain distance in order to fill a hall of a certain size or cut a particular recording. Any type of gain or loss in any circuit may be expressed in decibels which provide a quick and accurate key to the operating conditions of the circuit. The advantage of using decibels is that it permits the simple addition of ratios to obtain complete gain and loss data whereas using E, I, or P ratios would involve multiplication and division. For example, it is easier to add 25 dB and 36 dB than it is to multiply the corresponding gain figures of 316.2 and 4000, to get the total gain of two amplifiers in cascade.

Related Pages: RF Cafe Decimal Tutorial

|

The Decibel Without Pain |

Using the Decibel | Decibel Tutorial:

dB and dBm vs. Gain and Milliwatts |

Versatile Voltage, Power, and Decibel Nomograms |

Decibel Level

vs. Decibel Gain |

A Decibel

Nomograph | The Decibel: AWG Wire

Size Rule of Thumb |

What is a Decibel? |

Understanding Decibels |

Decibels Without Logs |

The Useful Decibel | Decibels |

mW-to-dBm / dBm-to-mW Power Conversion |

NEETS: Decibel

Posted August 11, 2022 |

|